Introduction to Docker

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Create first docker container

- Docker commands

- Dockerfile

- Docker Hub

- Private Registry

- Storing data

- Save and load images

- Additional resources

- References

- Credits

Introduction

Docker is a platform for developers and sysadmins to develop, deploy, and run applications with containers. The use of Linux containers to deploy applications is called containerization.

Containers are not new, but their use for easily deploying applications is.

Containerization is popular because containers are:

- Flexible: Even the most complex applications can be containerized

- Lightweight: Containers leverage and share the host kernel

- Portable: You can build locally, deploy to the cloud, and run anywhere

- Scalable: You can increase and automatically distribute container replicas

- Stackable: You can stack services vertically and on-the-fly

FYI: I didn’t write the above content. It’s from Docker. They’ve explained it pretty well and its concise.

A Docker container is a software bucket comprising everything necessary to run the software independently. There can be multiple Docker containers in a single machine and containers are completely isolated from one another as well as from the host machine. In other words, a Docker container includes a software component along with all of its dependencies (binaries, libraries, configuration files, scripts, jars, and so on).

Difference between containerization and virtualization

| Virtual Machines (VMs) | Containers |

|---|---|

| Represents hardware-level virtualization | Represents operating system virtualization |

| Heavyweight | Lightweight |

| Slow provisioning | Real-time provisioning and scalability |

| Limited performance | Native performance |

| Fully isolated and hence more secure | Process-level isolation and hence less secure |

-

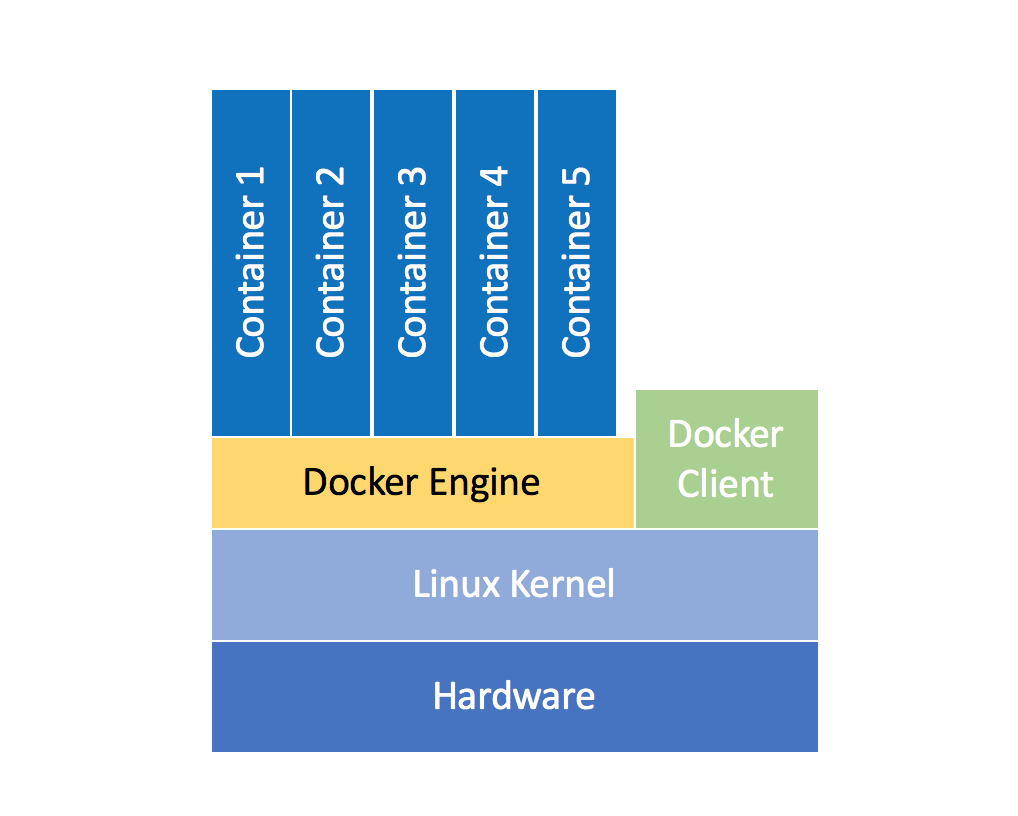

A docker container runs natively on Linux and shares the kernel of the host machine with other containers. It runs a discrete process, taking no more memory than any other executable, making it lightweight.

-

A virtual machine (VM) runs a full-blown guest operating system with virtual access to host resources through a hypervisor. In general, VMs provide an environment with more resources than most applications need

Installing Docker

Docker has several dependencies and platforms to support. Hence, it’s difficult to have one permalink for installers on different platforms. Instead, it’s better to watch out for official Docker Installation Documentation and pick your platform for latest installation guide.

If something doesn’t work, watch their release notes space as well. They tend to push changes that may break existing installations

NOTE: Before you accept a Docker upgrade on Ubuntu/CentOS/Debian/Fedora,

please check their release notes to see if they have a dependency change.

They broke my perfectly working Docker on Ubuntu 14.04 with their 18.06.3

release with an

explantion.

It required Ubuntu 14.04 customers using a 3.13 kernel will need to upgrade to

a supported Ubuntu 4.x kernel. Of course, security is important and upgrade

SHOULD be done. But, be careful and watch out for such upgrades.

Docker terminology

-

Docker Image is a docker executable package that includes everything needed to run an application–the code, a runtime, libraries, environment variables, and configuration files. It is an immutable, read-only file with instructions for creating a Docker container. Each change that is made to the original image is stored in a separate layer. To be precise, any Docker image has to originate from a base image according to the various requirements. Each time you commit to a Docker image you are creating a new layer on the Docker image, but the original image and each pre-existing layer remains unchanged.

-

Docker container is the running instance of a container image. Every time you start a container based on a container image file, you will get the exact same Docker container - no matter where you deploy it. This allows developers to solve the “works on my machine” issue. It also allows for greater collaboration as container images can be easily shared amongst developers and managed in image repositories like Docker Hub or within an enterprise in a secure, private repository

-

Docker Registry is a place where the Docker images can be stored in order to be publicly found, accessed, and used by the worldwide developers for quickly crafting fresh and composite applications without any risks. As a clarification, the registry is for registering the Docker images, whereas the repository is for storing those registered Docker images in a publicly discoverable and centralized place. A Docker image is stored within a Repository in the Docker Registry. Each Repository is unique for each user or account.

-

Docker Repository is a namespace that is used for storing a Docker image. For instance, if your app/image is named

helloworldand your username or namespace for the Registry isthedockeruserthen the image would be stored in Docker Registry with the namethedockeruser/helloworld -

Docker Hub is a service provided by Docker for finding and sharing container images with other developers. It provides the following major features:

- Repositories: Push and pull container images

- Official Images: Pull and use high-quality container images provided by Docker

- Publisher Images: Pull and use high-quality container images provided by external vendors.

- Builds: Automatically build container images from GitHub and Bitbucket and push them to Docker Hub

- Webhooks: Trigger actions after a successful push to a repository to integrate Docker Hub with other services.

The good folks in Docker community have built a repository of images and they

have made it publicly available at a default location (Docker index),

https://hub.docker.com/. The Docker Index is the official repository that

contains all the painstakingly curated images that are created and deposited

by the worldwide Docker development community.

As of 03/21/2019, there are over 2,098,068 images available! Check it out

In addition to the official repository, the Docker Hub Registry also provides a

platform for the third-party developers (You and me) and providers for sharing

their images for general consumption. The third-party images are prefixed by

the user ID of their developers or depositors. For example,

thedockeruser/helloworld is a third-party image, wherein thedockeruser is

the user ID and helloworld is the image repository name.

Apart from the preceding repository, the Docker ecosystem also provides a

mechanism for leveraging the images from any third-party repository hub other

than the Docker Hub Registry, and it provides the images hosted by the local

repository hubs. A manual repository path is similar to a URL without a

protocol specifier, such as https://, http:// and ftp://. Following

is an example of pulling an image from a third party repository hub:

$ docker pull registry.example.com/myapp

Create first docker container

$ docker pull hello-world

Using default tag: latest

latest: Pulling from library/hello-world

1b930d010525: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:2557e3c07ed1e38f26e389462d03ed943586f744621577a99efb77324b0fe535

Status: Downloaded newer image for hello-world:latest

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

hello-world latest fce289e99eb9 2 months ago 1.84kB

$ docker run hello-world

Hello from Docker!

This message shows that your installation appears to be working correctly.

To generate this message, Docker took the following steps:

1. The Docker client contacted the Docker daemon.

2. The Docker daemon pulled the "hello-world" image from the Docker Hub.

(amd64)

3. The Docker daemon created a new container from that image which runs the

executable that produces the output you are currently reading.

4. The Docker daemon streamed that output to the Docker client, which sent it

to your terminal.

To try something more ambitious, you can run an Ubuntu container with:

$ docker run -it ubuntu bash

Share images, automate workflows, and more with a free Docker ID:

https://hub.docker.com/

For more examples and ideas, visit:

https://docs.docker.com/get-started/

The docker pull subcommand is programmed to look for the images on DockerHub.

Therefore, when you pull a hello-world image, it is effortlessly

downloaded from the default registry. This mechanism helps in speeding up the

spinning of the Docker containers.

Docker commands

Searching Docker images

Docker Hub repository typically hosts both the official images as well as the

images that have been contributed by the third-party Docker enthusiasts. These

images can be used either as is, or as a building block for the user-specific

applications. You can search for the Docker images in the Docker Hub Registry

by using the docker search subcommand, as shown in this example:

$ docker search tensorflow

NAME DESCRIPTION STARS OFFICIAL AUTOMATED

tensorflow/tensorflow Official Docker images for the machine learn… 1345

jupyter/tensorflow-notebook Jupyter Notebook Scientific Python Stack w/ … 118

...

$ docker search lamp

NAME DESCRIPTION STARS OFFICIAL AUTOMATED

linode/lamp LAMP on Ubuntu 14.04.1 LTS Container 167

tutum/lamp Out-of-the-box LAMP image (PHP+MySQL) 114

greyltc/lamp a super secure, up-to-date and lightweight L… 95 [OK]

...

$ docker search nginx

NAME DESCRIPTION STARS OFFICIAL AUTOMATED

nginx Official build of Nginx. 11096 [OK]

jwilder/nginx-proxy Automated Nginx reverse proxy for docker con… 1567 [OK]

...

Logging into a Docker container

The docker run subcommand takes an image as an input and launches it as a

container. You have to pass the -t and -i flags to the docker run

subcommand in order to make the container interactive. The -i flag is the key

driver, which makes the container interactive by grabbing the standard input

(STDIN) of the container. The -t flag allocates a pseudo-TTY or a pseudo

terminal (terminal emulator) and then assigns that to the container.

Example:

$ docker run --help | grep "\-interactive"

-i, --interactive Keep STDIN open even if not attached

$ docker run --help | grep "\-tty"

-t, --tty Allocate a pseudo-TTY

$ docker run -t -i ubuntu /bin/bash

Unable to find image 'ubuntu:latest' locally

latest: Pulling from library/ubuntu

d5c6f90da05d: Pull complete

...

root@6ff30c656fb0:/# cat /etc/lsb-release

DISTRIB_ID=Ubuntu

DISTRIB_RELEASE=16.04

DISTRIB_CODENAME=xenial

DISTRIB_DESCRIPTION="Ubuntu 16.04.3 LTS"

root@6ff30c656fb0:/#

Detaching/Attaching from/to a Container

We can detach from our container by using the Ctrl + P and Ctrl + Q escape

sequence from within the container. This escape sequence will detach the TTY

from the container and land us in the Docker host prompt $, however the

container will continue to run. The docker ps subcommand will list all the

running containers and their important properties, as shown here:

$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

6ff30c656fb0 ubuntu "/bin/bash" 3 minutes ago Up 3 minutes eloquent_clarke

The Docker engine auto-generates a random container name by concatenating an

adjective and a noun. Either the container ID or its name can be used to take

further action on the container. The container name can be manually configured

by using the --name option in the docker run subcommand.

Having looked at the container status, let’s attach it back to our container by

using the docker attach subcommand as shown in the following example.

$ docker attach eloquent_clarke

root@6ff30c656fb0:/#

Detecting file system changes on a running container

Just run docker diff <container_ID or container_name> from another terminal

Example:

$ docker run -it --name testing ubuntu /bin/bash

root@f391999f49e3:/# cd /home

root@f391999f49e3:/home# touch a b c

Open another terminal

$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

f391999f49e3 ubuntu "/bin/bash" About a minute ago Up About a minute testing

$ docker diff testing

A /home/a

A /home/b

A /home/c

Stop a container

Open another terminal while the container testing is running

$ docker stop testing

testing

Start and attach to a stopped container

$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

f391999f49e3 ubuntu "/bin/bash" 5 minutes ago Exited (0) About a minute ago testing

$ docker start testing

testing

$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

f391999f49e3 ubuntu "/bin/bash" 5 minutes ago Up 8 seconds testing

$ docker attach testing

root@f391999f49e3:/#

root@f391999f49e3:/# ls /home

a b c

Container pause/unpause

Sometimes you may wish to leave a container process paused and not terminate. For such cases, you may wish to pause a container and unpause it later when you have time to look at it. Think of it as hibernation.

docker pause testing

testing

$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

f391999f49e3 ubuntu "/bin/bash" 8 minutes ago Up 2 minutes (Paused) testing

$ docker unpause testing

testing

Removing/Deleting containers (Container Housekeeping)

When we issue docker ps -a we may see many stopped containers. These

containers could continue to stay in the stopped status for ages, if we choose

not to intervene. At the outset, it may look like a glitch, but in reality, we

can perform operations, such as committing an image from a container,

restarting the stopped container, and so on. However, not all the stopped

containers will be reused, and each of these unused containers will take up

disk space in the filesystem of the Docker host. The Docker engine provides a

couple of ways to alleviate this issue.

During a container startup, we can instruct the Docker engine to clean up the

container as soon as it reaches the stopped state. For this purpose,

the docker run subcommand supports an --rm option

(for example: sudo docker run -i -t --rm ubuntu /bin/bash).

The other alternative is to list all the containers by using

docker ps -a subcommand and then manually remove them by using the

docker rm subcommand, as shown here:

$ docker rm admiring_brown

admiring_brown

$ docker rm admiring_leakey

admiring_leakey

Alternatively, docker rm and docker ps, could be

combined to automatically delete all the containers that are not currently

running, as shown in the following command:

$ docker rm `docker ps -aq`

f391999f49e3

643e3cbeaf8b

6ff30c656fb0

b430b51785ba

0845d32134d6

$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

Create Image from containers

Let’s say you want to create your custom image with curl installed on an

Ubuntu distribution.

- Create a container with Ubuntu as base image

sudo apt-get update && sudo apt-get install -y curl- Exit the container

- Commit the container to an image

curlubuntu(or any other name)

$ docker run -it --name container_to_image ubuntu /bin/bash

root@cf918b1e5e79:/# apt-get update && apt-get install -y curl

Reading package lists... Done

Building dependency tree

Reading state information... Done

...

root@cf918b1e5e79:/# which curl

/usr/bin/curl

root@cf918b1e5e79:/# exit

exit

$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

cf918b1e5e79 ubuntu "/bin/bash" 47 seconds ago Exited (0) 2 seconds ago container_to_image

$ docker commit container_to_image learningdocker/curlubuntu

sha256:bda679a8b461273a646514cf411f9951ffa02385729130ca3062a9dcd702c9f6

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

learningdocker/curlubuntu latest bda679a8b461 8 seconds ago 175MB

ubuntu latest ccc7a11d65b1 6 days ago 120MB

We have committed our image by using the name `learningdocker/curlubuntu`.

If we decide to push this image to dockerhub, it will be pushed to

a user ID/repository named `learningdocker` and the name of the image would be

`curlubuntu`.

Using the newly created image:

```bash

$ docker run -t -i --name my_custom_container learningdocker/curlubuntu

root@9fbd3eceeee5:/# which curl

/usr/bin/curl

Launch container as daemon

Let’s say you wish to run a container with a web server listening for requests

on a particular port. For such use cases, you don’t need to enter the

interactive mode using /bin/bash. You just wish to run this container in the

background. We can use -d option to do this.

$ docker run -d -t -i --name testingdaemons learningdocker/curlubuntu

839853acb4faa51d48265c5c42ce5a262fcfef8da2df6d64545e5c8107cd1370

$ docker ps

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

839853acb4fa learningdocker/curlubuntu "/bin/bash" 2 seconds ago Up 1 second testingdaemons

Check size of container

Use the option -s for docker ps subcommand

$ docker ps -sa

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES SIZE

0bc97d321d78 ubuntu "/bin/bash" 8 minutes ago Exited (0) 2 seconds ago container_to_image 96.3MB (virtual 216MB)

size: the amount of data (on disk) that is used for the writable layer of

each container

virtual size: the amount of data used for the read-only image data used by

the container. Multiple containers may share some or all read-only image data.

Two containers started from the same image share 100% of the read-only data,

while two containers with different images which have layers in common share

those common layers. Therefore, you can’t just total the virtual sizes.

Dockerfile

Leveraging Dockerfile is the most competent way to build powerful images for

the software development community. Dockerfile is a text-based build script

that contains special instructions in a sequence for building the right and

relevant images from the base images. The sequential instructions inside the

Dockerfile can include the base image selection, installing the required

application, adding the configuration and the data files, and automatically

running the services as well as exposing those services to the external world.

It also offers a great deal of flexibility in the way in which the build

instructions are organized and in the way in which they visualize the complete

build process.

Let’s create a simple Dockerfile and see the process:

$ cat Dockerfile

FROM ubuntu

CMD echo "hello world"

$ docker build -t anewimage .

Sending build context to Docker daemon 2.048kB

Step 1/2 : FROM ubuntu

latest: Pulling from library/ubuntu

Digest: sha256:34471448724419596ca4e890496d375801de21b0e67b81a77fd6155ce001edad

Status: Downloaded newer image for ubuntu:latest

---> ccc7a11d65b1

Step 2/2 : CMD echo "hello world"

---> Running in 48523c39f8cf

---> a284393b7fe5

Removing intermediate container 48523c39f8cf

Successfully built a284393b7fe5

Successfully tagged anewimage:latest

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

anewimage latest a284393b7fe5 2 seconds ago 120MB

ubuntu latest ccc7a11d65b1 6 days ago 120MB

More explanation: A Docker image is built up from a series of layers. Each layer represents an instruction in the image’s Dockerfile. Each layer except the very last one is read-only. Consider the following Dockerfile:

FROM ubuntu:15.04

COPY . /app

RUN make /app

CMD python /app/app.py

This Dockerfile contains four commands, each of which creates a layer.

FROMstatement starts out by creating a layer from theubuntu:15.04image.COPYcommand adds some files from your Docker client’s current directory.RUNcommand builds your application using themakecommand.- Finally, the last layer specifies what command to run within the container.

Each layer is only a set of differences from the layer before it. The layers

are stacked on top of each other. When you create a new container, you add a

new writable layer on top of the underlying layers. This layer is often called

the “container layer”. All changes made to the running container, such as

writing new files, modifying existing files, and deleting files, are written to

this thin writable container layer.

Finally, all these changes are committed to a new image which can be named

using -t option during build.

Dockerfile syntax

A Dockerfile is made up of instructions, comments, and empty lines

# Comment

INSTRUCTION arguments

The instruction line of Dockerfile is made up of two components,

- instruction itself, followed by the

- arguments for the instruction.

The instruction is case-insensitive. However, the standard practice is to use uppercase in order to differentiate it from the arguments.

Example:

# This is a comment

# FROM <image>[:<tag>]

FROM busybox:latest

MAINTAINER John Doe <johndoe@gmail.com>

CMD echo Hello World!!

COPY

COPY <src> ... <dst>

<src>: This is the source directory, directory from where the docker build

subcommand was invoked.

...: This indicates that multiple source files can either be specified

directly or be specified by wildcards.

<dst>: This is the destination path for the new image into which the source

file or directory will get copied. If multiple files have been specified, then

the destination path must be a directory and it must end with a slash /.

ADD

ADD <src> ... <dst>

ADD instruction is similar to the COPY instruction. However, in addition to

the functionality supported by the COPY instruction, the ADD instruction

can handle the TAR files and remote URLs. We can annotate the ADD instruction

as COPY on steroids.

Thus the TAR option of the ADD instruction can be used for copying multiple

files to the target image.

ENV

ENV <key> <value>

Example: ENV DEBUG_LVL 3

The ENV instruction sets an environment variable in the new image.

USER

USER <UID>|<UName>

The USER instruction sets the start up user ID or user name in the new image

WORKDIR

WORKDIR <dirpath>

WORKDIR instruction sets the starting directory of the image

RUN

`RUN <command>`

The general recommendation is to execute multiple commands by using one RUN

instruction.

This reduces the layers in the resulting Docker image because the Docker system inherently creates a layer for each time an instruction is called in

Dockerfile

RUN instruction has two types of syntax:

- The first is the shell type, as shown here:

RUN <command>Here, the

<command>is the shell command that has to be executed during build time. If this type of syntax is to be used, then the command is always executed by using/bin/sh -c - The second syntax type is either exec or the JSON array, as shown here:

RUN ["<exec>", "<arg-1>", ..., "<arg-n>"]<exec>: This is the executable to run during the build time

<arg-1>, ..., <arg-n>: These are the variables (zero or more) number of the arguments for the executable.

Unlike the first type of syntax, this type does not invoke/bin/sh -c. Therefore, the types of shell processing, such as the variable substitution ($USER) and the wild card substitution (*,?), do not happen in this type. For example,RUN ["bash", "-c", "rm", "-rf", "/tmp/abc"].

Sample uses of RUN:

# Install apache2 package

RUN apt-get update && \

apt-get install -y apache2 && \

apt-get clean

CMD

CMD <command>

CMD instruction can run any command (or application), which is similar to

RUN instruction. However, the major difference between those two is the

time of execution. Command supplied through RUN instruction is executed

during the build time, whereas the command specified through CMD instruction

is executed when the container is launched from the newly created image.

Therefore, CMD instruction provides a default execution for a container.

Syntactically, you can add multiple

CMDinstructions inDockerfile. However, the build system would ignore all theCMDinstructions except for the last one. In other words, only the lastCMDinstruction would be effective

Usage example:

$ cat Dockerfile

FROM ubuntu

CMD echo "hello world"

CMD date

$ docker build -t testing .

Sending build context to Docker daemon 3.072kB

Step 1/4 : FROM ubuntu

...

Successfully built ef2427a4ee54

Successfully tagged testing:latest

$ docker run testing

Thu Aug 17 00:52:07 UTC 2017

ENTRYPOINT

Official docker documentation has the best explanation Here’s an excerpt:

ENTRYPOINT has two forms:

ENTRYPOINT ["executable", "param1", "param2"](exec form, preferred)ENTRYPOINT command param1 param2(shell form)

An ENTRYPOINT allows you to configure a container that will run as an

executable.

Example usage in a Dockerfile :

ENTRYPOINT ["/usr/sbin/apache2ctl", "-D", "FOREGROUND"]

ENTRYPOINT and CMD have some combinations and I’m pretty sure it

shouldn’t be a part of 101 series. Check it out

.dockerignore file

docker build process will send the complete build context to the daemon.

In a practical environment, the command context will contain many other

working files and directories, which would never be built into the image.

Nevertheless, the docker build system would still send those files to the

daemon.

.dockerignore is a newline-separated TEXT file, wherein you can provide the

files and the directories which are to be excluded from the build process.

Example contents from a .dockerignore file:

.git

*.tmp

Docker Hub

It’s super easy to create your image and push to your public dockerhub repository. I guess you get just 1 private repository with a free account.

- Sign up for a free docker hub account

- Open the terminal and sign in to Docker Hub on your host by running

$ docker login Login with your Docker ID to push and pull images from Docker Hub. If you don't have a Docker ID, head over to https://hub.docker.com to create one. Username: docker_user_000 Password: Login Succeeded - Create a

Dockerfilewith any operations you want$ cat > Dockerfile <<EOF FROM busybox CMD echo "Hello world! This is my first Docker image." EOF - Run

docker build -t <your_username>/my-first-repo .to build your Docker image - Run

docker push <dockerhub_username>/my-first-repoto push your Docker image to Docker Hub - In Docker Hub, your repository should have a new latest tag available under Tags

- Alternatively, you may also commit any stopped/running container to a docker image and push that image

Push sample Dockerfile image to Docker Hub

$ cat Dockerfile

FROM busybox

CMD echo "Hello world! This is my first Docker image."

$ docker build -t <dockerhub_username>/my_first_repo .

Sending build context to Docker daemon 2.048kB

Step 1/2 : FROM busybox

latest: Pulling from library/busybox

697743189b6d: Pull complete

Digest: sha256:061ca9704a714ee3e8b80523ec720c64f6209ad3f97c0ff7cb9ec7d19f15149f

Status: Downloaded newer image for busybox:latest

---> d8233ab899d4

Step 2/2 : CMD echo "Hello world! This is my first Docker image."

---> Running in 88c2867668fa

Removing intermediate container 88c2867668fa

---> 9dfc4add437d

Successfully built 9dfc4add437d

Successfully tagged <dockerhub_username>/my_first_repo:latest

$ docker push <dockerhub_username>/my_first_repo

The push refers to repository [docker.io/<dockerhub_username>/my_first_repo]

adab5d09ba79: Mounted from library/busybox

latest: digest: sha256:fee905a216aa7ff798300aa8001c272ef5a047bd61ee24a8268446391dd9153c size: 527

Push running/stopped container to Docker Hub

$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

010eec8cd9f1 testing "/bin/bash" 2 hours ago Up 2 hours angry_poincare

$ docker commit 010eec8cd9f1 awesome_name

sha256:1668d121b5e1574341a8831ddefeff5a2cc4b81aea29a91763d3a7567c25964f

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

awesome_name latest 1668d121b5e1 10 seconds ago 81.2MB

ubuntu latest 113a43faa138 9 months ago 81.2MB

$ docker tag awesome_name <dockerhub_username>/test_repo

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

awesome_name latest 1668d121b5e1 31 seconds ago 81.2MB

<dockerhub_username>/test_repo latest 1668d121b5e1 31 seconds ago 81.2MB

ubuntu latest 113a43faa138 9 months ago 81.2MB

$ docker push <dockerhub_username>/test_repo

The push refers to repository [docker.io/<dockerhub_username>/test_repo]

479a19fa4d78: Pushed

...

latest: digest: sha256:283365c897d07d0af20f17c49f27ec91108d853a78c56c4e83f4d5130a84de20 size: 1564

REMEMBER: The name format for an image should be

<dockerhub_username>/<repo_name>[:version]in order to push to Docker Hub. If the name is not in the format, you can always usedocker tag <image_id> <new_name>

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

ubuntu latest 113a43faa138 9 months ago 81.2MB

$ docker tag 113a43faa138 any_name_1

$ docker tag 113a43faa138 any_name_2

$ docker tag 113a43faa138 any_name_3

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

any_name_1 latest 113a43faa138 9 months ago 81.2MB

any_name_2 latest 113a43faa138 9 months ago 81.2MB

any_name_3 latest 113a43faa138 9 months ago 81.2MB

ubuntu latest 113a43faa138 9 months ago 81.2MB

$ docker rmi any_name_1

Untagged: any_name_1:latest

$ docker rmi any_name_2

Untagged: any_name_2:latest

$ docker rmi any_name_3

Untagged: any_name_3:latest

Also, make sure you remove all the tags before removing the original image using image_id

Testing the pushed repository

- Remove the local image from your host

$ docker rmi <dockerhub_username>/my_first_repo - Pull the remote repo

$ docker run <dockerhub_username>/my_first_repo Unable to find image '<dockerhub_username>/my_first_repo:latest' locally latest: Pulling from <dockerhub_username>/my_first_repo 6b98dfc16071: Already exists ... 4b8e422ee13e: Pull complete Digest: sha256:283365c897d07d0af20f17c49f27ec91108d853a78c56c4e83f4d5130a84de20 Status: Downloaded newer image for <dockerhub_username>/my_first_repo:latest

Automate build process for Docker Hub images

Docker Hub can automatically build the image from Dockerfile kept in the

Github/Bitbucket repository. Automated builds are supported on both private and

public repositories. All you need to do is connect with Github and provide

permissions (private/public) and create a new project on Github with

Dockerfile.

So, whenever Dockerfile is updated on GitHub, the automated build gets

triggered, and a new image will be stored in the Docker Hub Registry. We

can always check the build history.

I think this is one of the coolest features of Docker Hub. Just imagine this. You alter a few lines in a file, install applications, install firewall, update a version of product, do whatever and just one regular push to Github will trigger an automatic build and give you a shiny brand new image (hosted free on Docker Hub). That is severely cool.

Private Registry

Docker has been cool enough to allow enterprises/developers to create their own private registries (hosted privately). Normally, enterprises will not like to keep their Docker images in a public Docker registry. They prefer to keep, maintain, and support their own registry.

- Create a container using a base image

$ docker run -t -i --name firstprivatecontainer ubuntu /bin/bash root@1a6cc385dd14:/# useradd -m testuser root@1a6cc385dd14:/# cd /home/testuser/ root@1a6cc385dd14:/home/testuser# echo "firstfile"> firstfile.txt root@1a6cc385dd14:/home/testuser# exit exit - Commit the change to create your private image

$ docker commit firstprivatecontainer first_private_image sha256:d1673af8e0bf6b609214f73205bdc5f811a0e3152678719dc1946e5ef377732b $ docker images REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE first_private_image latest d1673af8e0bf 4 seconds ago 120MB ubuntu latest ccc7a11d65b1 6 days ago 120MB - For remote private repositories, there is a convention of tagging the images

which is mandatory. You won’t be able to push private images to your remote

private registries unless you follow the following naming convention :

<remoteIP/hostname>:<portnumber>/<anyname>.

If the image is not tagged, usedocker tagto create a new tag:$ docker tag rhel-httpd registry-host:5000/rhel-httpd - Tag your image to match the convention

$ docker tag first_private_image <privateIP>:5000/first_private_image - Before we push to our remote private repository, we have to perform a few

steps

- Make sure the remote IP has a

registrycontainer running in daemon mode listening on port 5000 (or any private port)# Remote private registry hosting machine # Start a private registry container on the remote machine $ docker run -d -p 5000:5000 --name registry registry:2 - Make sure you add the following to a new/existing file

/etc/docker/daemon.jsonon the client (from where you are pushing the images)$ sudo cat /etc/docker/daemon.json { `"insecure-registries" : ["<privateIP>:5000"] } - Restart the docker:

$ sudo service docker restart - This will help the client to trust that private IP to push to its registries

FYI: The process is different for MacOS. Please don’t ask about Windows (I’ve no idea)

- Make sure the remote IP has a

- Push the private image to our remote registry

$ docker push <privateIP>:5000/first_private_image The push refers to a repository [<privateIP>:5000/first_private_image] ... 8aa4fcad5eeb: Pushed latest: digest: sha256:2f129d4de7a628078c8d5dba4f1e7e6d72c0a4cf956518d0446f33cadb1b7f86 size: 1565

Private registry T&C

- The remote private repositories are only good until the

registrycontainer runs in daemon-dmode on the remote host - The minute you bring down the

registrycontainer, you lose access to ALL saved images in that repository - Checking the existing images on a remote private repository from any client:

$ curl -X GET http://<privateIP>:5000/v2/_catalog| python -mjson.tool % Total % Received % Xferd Average Speed Time Time Time Current Dload Upload Total Spent Left Speed 100 64 100 64 0 0 13039 0 --:--:-- --:--:-- --:--:-- 16000 { "repositories": [ "first_private_image", "second_private_image" ] }

Storing data

Ever wondered what happens to the files/directories created in a container

when the container dies? (docker rm <container_id>). Also, how do you

access container data from your host machine? Here are the answers:

When a Docker container is destroyed, it’s entire file system is destroyed too. If the container has been stopped, you are in luck and you can pick it up from where you left. But if you have destroyed the container, the data is gone. Not even Docker’s founders can retrieve it back for you.

When we create a new container, we add a new & thin writable layer on top of the underlying stack of layers present in the base docker image. All changes made to the running container, such as creating new files, modifying existing files or deleting files, are written to this thin writable container layer.

Just imagine a container on a large ship. If you open a container (start container), put a Rolls-Royce in it (Create files/directories), and close the container (stop the container), your car is safe. However, if you decide that container is heavy and you drop it into Mariana Trench, the container takes down your Rolls-Royce with it.

Docker has two options for containers to store files in the host machine, so that the files are persisted even after the container stops/dies:

- Volumes

- Stored in a part of the host filesystem which is managed by Docker

(

/var/lib/docker/volumes/on Linux) - Volumes are the best way to persist data in Docker

- Created and managed by Docker

- A given volume can be mounted into multiple containers simultaneously

- When no running container is using a volume, the volume is still available to Docker and is not removed automatically

- Volumes also support the use of volume drivers, which allow you to store your data on remote hosts or cloud providers, among other possibilities

- You can also encrypt a volume

- A volume does not increase the size of the containers using it, and the volume’s contents exist outside the lifecycle of a given container

- Stored in a part of the host filesystem which is managed by Docker

(

- Bind mounts

- Stored anywhere on the host system

- Limited functionality compared to volumes

- When you use a bind mount, a file or directory on the host machine is mounted into a container

- You can’t use Docker CLI commands to directly manage bind mounts

If you’re running Docker on Linux you can also use a tmpfs mount. tmpfs mounts are stored in the host system’s memory only, and are never written to the host system’s filesystem.

When to use Docker volumes?

- Sharing data among multiple running containers. When that container stops or is removed, the volume still exists. Multiple containers can mount the same volume simultaneously, either read-write or read-only. Volumes are only removed when you explicitly remove them.

- When you want to store your container’s data on a remote host or a cloud provider, rather than locally

- When you need to back up, restore, or migrate data from one Docker host to another, volumes are a better choice

When to use bind mount?

- Sharing configuration files from the host machine to containers

- Sharing source code or build artifacts between a development environment on the Docker host and a container

Options to use volumes and bind mounts

-v or --volume: Consists of three fields, separated by colon

characters (:).

The fields must be in the correct order.

- In the case of named volumes, the first field is the name of the volume, and is unique on a given host machine. For anonymous volumes, the first field is omitted. In case of bind mounts, the first field is the path to the file or directory on the host machine.

- The second field is the path where the file or directory are mounted in the container.

- The third field is optional, and is a comma-separated list of options, such

as

ro,consistent,delegated,cached,z, andZ

--mount: Consists of multiple key-value pairs, separated by commas and each

consisting of a <key>=<value> tuple. The --mount syntax is more verbose

than -v or --volume, but the order of the keys is not significant, and the

value of the flag is easier to understand.

typeof the mount, which can bebind,volume, ortmpfs.- Source of the mount. For named volumes, this is the name of the volume. For

anonymous volumes, this field is omitted. May be specified as

sourceorsrc. For bind mounts, this is the path to the file or directory on the Docker daemon host - Destination takes as its value the path where the file or directory is

mounted in the container. May be specified as

destination,dst, ortarget.

Some advanced options are not mentioned here for brevity

Differences between -v and --mount

Due to the overlap of concept names and options, it might be a little

tricky to explain the differences between -v and --mount.

For example: We can bind mount a host directory using --volume option.

We can create a Docker volume by using --mount option.

It’s helpful if you can just treat these two things as separate.

Anyway, here’s the difference:

- If you use

-vor--volumeto bind-mount a file or directory that does not yet exist on the Docker host, -v creates the endpoint for you. It is always created as a directory. - If you use

--mountto bind-mount a file or directory that does not yet exist on the Docker host, Docker does not automatically create it for you, but generates an error.

Enough theory, let’s see some action!

Let’s walk through some quick examples to check out the data persistency concepts of Docker

All of these examples are valid on Linux machines. Check out Docker documentation for MacOS instructions and I don’t care about windows.

- Create anonymous volume

# Create container with anonymous volume $ docker run -it -v /data ubuntu /bin/bash # Create some random data in the volume root@6d6557df9c78:/# dd if=/dev/urandom of=/data/random.data ^C19800+0 records in 19799+0 records out 10137088 bytes (10 MB, 9.7 MiB) copied, 0.821677 s, 12.3 MB/s root@6d6557df9c78:/# ls -la /data/ total 9908 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mar 22 21:05 . drwxr-xr-x 34 root root 4096 Mar 22 21:05 .. -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 10137088 Mar 22 21:05 random.data root@6d6557df9c78:/# exit exit # Check out the unnamed volume in your host $ docker volume ls DRIVER VOLUME NAME local 979318647fabc18f651dd166d46e0cd801e9667c2acd516fbb3e0f583bf66e37 # Get the storage location of this volume on your host $ docker volume inspect 979318647fabc18f651dd166d46e0cd801e9667c2acd516fbb3e0f583bf66e37 [ { "CreatedAt": "2019-03-22T14:05:32-07:00", "Driver": "local", "Labels": null, "Mountpoint": "/var/lib/docker/volumes/979318647fabc18f651dd166d46e0cd801e9667c2acd516fbb3e0f583bf66e37/_data", "Name": "979318647fabc18f651dd166d46e0cd801e9667c2acd516fbb3e0f583bf66e37", "Options": null, "Scope": "local" } ] # Destroy your used container $ docker ps -a CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES 6d6557df9c78 ubuntu "/bin/bash" 59 seconds ago Exited (0) 35 seconds ago modest_torvalds $ docker rm 6d 6d # Check if the data persists in your volume $ sudo ls -la /var/lib/docker/volumes/979318647fabc18f651dd166d46e0cd801e9667c2acd516fbb3e0f583bf66e37/_data/ [sudo] password for <username>: total 9908 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mar 22 14:05 . drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 Mar 22 14:05 .. -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 10137088 Mar 22 14:05 random.data - Create named volume

# Create a container with a named volume tmp-volume and create 3 files $ docker run -v tmp-volume:/data ubuntu touch /data/file1 /data/file2 /data/file3 # The container has exited, check the volume location $ docker volume ls DRIVER VOLUME NAME local tmp-volume $ docker volume inspect tmp-volume [ { "CreatedAt": "2019-03-22T14:16:17-07:00", "Driver": "local", "Labels": null, "Mountpoint": "/var/lib/docker/volumes/tmp-volume/_data", "Name": "tmp-volume", "Options": null, "Scope": "local" } ] # Destroy the container $ docker ps -a CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES 97dbab2696ae ubuntu "touch /data/file1 /…" 46 seconds ago Exited (0) 45 seconds ago eloquent_snyder $ docker rm 97dbab2696ae 97dbab2696ae # Check out the persistent files on your volume $ sudo ls -la /var/lib/docker/volumes/tmp-volume/_data total 8 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mar 22 14:16 . drwxr-xr-x 3 root root 4096 Mar 22 14:15 .. -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Mar 22 14:16 file1 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Mar 22 14:16 file2 -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 0 Mar 22 14:16 file3 - Sharing volumes between containers

Terminal 1$ docker run -it -v tmp-volume:/data ubuntu /bin/bash root@7a4c01cfcbea:/# cd /data/ root@7a4c01cfcbea:/data# dd if=/dev/urandom of=random.data ^C12961+0 records in 12960+0 records out 6635520 bytes (6.6 MB, 6.3 MiB) copied, 0.540634 s, 12.3 MB/s root@7a4c01cfcbea:/data# ls -la random.data -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 6635520 Mar 22 21:35 random.dataTerminal 2

$ docker ps -a CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES 7a4c01cfcbea ubuntu "/bin/bash" 4 minutes ago Up 4 minutes elegant_blackwell # Run a container that shows data in /data mounted from volume $ docker run --rm --volumes-from 7a4c01cfcbea ubuntu ls -la /data total 6488 drwxr-xr-x 2 root root 4096 Mar 22 21:39 . drwxr-xr-x 34 root root 4096 Mar 22 21:39 .. -rw-r--r-- 1 root root 6635520 Mar 22 21:35 random.data - Mounting local file system on Docker

# Create sample data files in your current directory $ pwd <current_dir_path> $ touch file1 file2 $ ls file1 file2 # Mount your current directory with data files on docker container # show the files in /data and exit $ docker run --rm -v <current_dir_path>:/data ubuntu ls -la /data total 8 drwxrwxr-x 2 8367 8367 4096 Mar 22 21:41 . drwxr-xr-x 34 root root 4096 Mar 22 21:42 .. -rw-rw-r-- 1 8367 8367 0 Mar 22 21:41 file1 -rw-rw-r-- 1 8367 8367 0 Mar 22 21:41 file2Data created from within the container persists in this directory since you’re writing to the local file system

You can try out the same steps by using --mount and the behavior will remain

the same.

Oh BTW, if you end up creating several volumes and now want to delete them:

Stop running containers and use docker volume prune to remove all unused

volumes.

$ docker run -v tmp-vol1:/data ubuntu date

Fri Mar 22 21:48:51 UTC 2019

$ docker run -v tmp-vol2:/data ubuntu date

Fri Mar 22 21:48:56 UTC 2019

$ docker run -v tmp-vol3:/data ubuntu date

Fri Mar 22 21:49:01 UTC 2019

$ docker volume ls

DRIVER VOLUME NAME

local tmp-vol1

local tmp-vol2

local tmp-vol3

$ docker volume prune

WARNING! This will remove all local volumes not used by at least one container.

Are you sure you want to continue? [y/N] y

Total reclaimed space: 0B

If you wish to remove anonymous volumes associated with a container, you may use

docker rm -v option. However, this doesn’t work on named volumes.

# Create an anonymous volume

$ docker run -v /data ubuntu date

Fri Mar 22 21:58:54 UTC 2019

# Check the unnamed volume

$ docker volume ls

DRIVER VOLUME NAME

local 5c7d4a1acf4bd2afcab8ff15c3b6f5f819845228aa09c2af09a8bdc6e7109aea

# Check the stopped container ID

$ docker ps -a

CONTAINER ID IMAGE COMMAND CREATED STATUS PORTS NAMES

6e73e62de4d2 ubuntu "date" 11 seconds ago Exited (0) 9 seconds ago silly_mahavira

# Destroy the container and the associated anonymous volume

$ docker rm -v 6e

6e

# Make sure the volume is destroyed

$ docker volume ls

DRIVER VOLUME NAME

There are some more interesting topics like Orchestration, Testing, Swarm, Services, Security etc but that’s may be for a 201 article. This is 101.

Save and load images

If we wish to create a portable image that can be distributed and used in remote machines, we can use save and load functionality in docker.

Export an image to a tar.gz

# Example

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

sample-service-image v0 acc8efacbbea 2 months ago 3.89GB

$ docker save sample-service-image | gzip > /tmp/sample-service-image.tar.gz

# Send the file to a remote destination

$ scp -i ~/.ssh/id_rsa /tmp/sample-service-image.tar.gz <remote_user>@<remote_host>:/tmp/

Load an image from a compressed file

# Remote host with compressed image file

$ docker load < /tmp/sample-service-image.tar.gz

174f56854903: Loading layer [==================================================>] 211.7MB/211.7MB

...

977b3f408ce3: Loading layer [==================================================>] 2.267GB/2.267GB

Loaded image: sample-service-image:v0

$ docker images

REPOSITORY TAG IMAGE ID CREATED SIZE

sample-service-image v0 acc8efacbbea 2 months ago 3.89GB

Additional resources

- Play with docker classroom

- Docker for developers

- Learn Docker & Containers using Interactive Browser-Based Scenarios

- Comprehensive docker cheat sheet

- r/docker

References

- Docker Documentation

- Understanding volumes

- docker run

- docker volume

- Docker Hub

- Dockerfile

- Linux Containers

- Understanding Linux Containers

- What’s a linux container?

Credits

- Solomon Hykes - Founder of Docker

- Documentation team at Docker for doing a fabulous job at creating Docker material