Public Key Cryptography

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- History

- Unsung heroes of Public Key Cryptography

- What’s private key cryptography?

- Why do we need Public key cryptography?

- What is RSA?

- Generate RSA public-private key pair

- DER, BER, PEM, ASN.1, X.509

- Public key cryptography for encryption

- Public cryptography for signing (digital signatures)

- Additional resources

Introduction

- Public key cryptography is used interchangeably with asymmetric cryptography; They both denote the exact same thing and are used synonymously

- Public key cryptography (Asymmetric Cryptography) involves a pair of keys known as a public key and a private key

- Public key is published and the corresponding private key is kept secret

- Data that is encrypted with the public key can be decrypted only with the corresponding private key

Before we get started, most of us have seen keys as something like this:

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

We may have some specific questions like:

[Q] What exactly is this key? Is it some random bytes? How does a key look like?

(Enough of visual representations!)

[A] They’re just numbers. Normal regular positive integers. However, they have very large number of digits. Wait no more, here is what a public and private key look like:

n = 2245944838578036526972583396448350551747843525119085870865837921064767862499

5080698551937025022186301711535333198664798188326624882731471433305369620049

9826334796240761090584167633432656265188647836110242553974179632080636660650

9553493655928231758714894373780618182801915185644831114898975050468805964483

6329930121323954250397233617250981771294652550666361750227000001163814082240

1213802131566884820219731159073117564151470164344800066475416917008836012841

6453999969381586227449891026404194967505712083340252860306641679640365774257

8899951399542059233818410379611323656680403814378526886221231167479535046352

291836079

e = 65537

d = 5438629261063741044456551032490856044103067998785402562009376048231970639160

6562809713481024017287426669219790021333040457870140056601378098868763579381

6049549600430425333410247698639891195590863353383516079706155417721242016651

7633389431860023804996471262324856273718112516011332498198992027547789898279

6367125516774011214449348835105146112524832528466786061288886908728901871761

7330798675702944198764135596823504891287070715575597029612982520978737317421

9386789071135476909410835408405212931007402450771425225993435533102280382944

3362040358826807748069982321379309636762497447239054568638341393733053187204

3814049

- The public key is made of the modulus n, and the public (or encryption) exponent e

- The private key is made of the modulus n, and the private (or decryption) exponent d, which must be kept secret

[Q] Wait, what? My public key looks like this…

$ cat id_rsa.pub

ssh-rsa AAAAB3NzaC1yc2EAAAADAQABAAAAgQCVAbPULFe/I7ZfAr+UqGS5FR5ymxE78mlR/DZO+mJV

TlXNR2Vt/FbCEWfIctiVWwDL2tL/y6eNlQNDu57tbwg+O7lgw5D6qz5ZaCd9WxIR2YCgcC+knHDCqnfq

b1wShK4jCP9dGy43BWKQT7mCrGSCK3a9Chu8fNlOiYPmZNBT1Q==

[A] Yeah, that’s public key in OpenSSH format. It contains the same n and e information. Scroll down further and you will learn more about formats of public key.

[Q] How can I use it?

[A] Interestingly enough, there’s a very high chance that you’ve already

used public key cryptography.

- Have you booked a holiday/flight on a reputed travel company website?

- Have you ever purchased something from amazon.com?

- Did a google search?

Chances are: your browser has used these keys on your behalf in the background while you waited for that product image to load on amazon or while you mindlessly scrolled on facebook to peek into others lives. Billions of people all over the planet use public key cryptography on a daily basis to establish secure connections to their banks, e-commerce sites, e-mail servers, and the cloud.

History

[Q] Why History? Isn’t it boring and just a collection of names, dates and events?

[A] I used to think so too. However, history of public key cryptography has

some valuable lessons for our present and future. It gives you the motivation

to solve new problems, identify patterns, and contribute to the world of

cryptography. Diffie-Hellman protocol or RSA

or any early protocols were answers to a 2000 year old (historic) symmetric key problem.

Knowing the history and the large scale impact of some historical discoveries gives you the motivation to solve new problems or to improve existing solutions.

Publicly introduced by Whitfield Diffie, Martin Hellman and Ralph Merkle in 1976. They also played a crucial role in ending the monopoly on cryptography. We may take it for granted now but this was a crucial defining moment in the history. Imagine a technically armed g-o-v-e-r-n-m-e-n-t that can read emails, whatsapp messages, text messages, photos, bank transactions, social life, credit card purchases, etc. It would lead to an efficient version of social credit score and that’s bad. Why? Because “Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?”. Anyway, let’s not digress further.

Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman are also the recipients of ACM Turing award.

The ACM Turing Award, often referred to as the “Nobel Prize of Computing,” carries a $1 million prize with financial support provided by Google, Inc.

Unsung heroes of Public Key Cryptography

In 1970, a cryptographer named James H.Ellis working for the UK’s Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) theorized about a public key encryption system (“non-secret encryption”) way before Diffie-Hellman protocol.

What Ellis called “non-secret encryption” we now call public key cryptography.

Ellis said that the idea first occurred to him after reading a paper from World War II by someone at Bell Labs describing a way to protect voice communications by the receiver adding (and then later subtracting) random noise. He realised that ‘noise’ could be applied mathematically but was unable to devise a way to implement the idea.

Now you see why history is not a mere collection of names, dates and events?

In 1973, on arriving at GCHQ, a mathematician Clifford Cocks was given Ellis’s internal report. He started working on it using his number theory background and within a very short time had invented the algorithm (now known as the RSA algorithm) that was to be identified four years later by Rivest, Shamir and Adleman. Clifford’s school friend, Malcolm John Williamson, had also joined GCHQ around this time, and he managed, after reading Ellis’s report, to come up with what we now know as the Diffie-Hellman protocol.

The story of this discovery was kept secret for a further 24 years. In 1997, Clifford announced to a conference the true history of the development of public key cryptography, and various internal reports were declassified to support the story. Alas, Ellis, whose original idea it had all stemmed from, died a few months before the announcement.

Just out of curiosity: Do we have access to those declassified documents from GCHQ?

Yes!

- The Possibility of Secure Non-Secret Encryption by James H.Ellis

- A Note on ‘Non-secret Encryption’ by Clifford Cocks

For some weird reason, the full PDF doesn’t load in Chrome. Works in Mozilla Firefox and Safari.

[Q] Have you read them?

[A] Not yet, it’s in my bucket list

What’s private key cryptography?

In Private key cryptography, both parties must hold on to a matching private key (or else exchange it upon transmission) to encipher and then decipher plaintext.

Basically, use the same key for encryption and decryption

Famous examples:

Why do we need Public key cryptography?

There is a major flaw inherent in private key cryptography. Today we refer to it as key distribution. If there was any distance between the two parties (which is not uncommon), you had to entrust a courier with your private key or travel there to exchange it yourself.

In a typical situation:

- Alice wants to send a message to Bob, and Eve is trying to eavesdrop.

- If Alice is sending private messages to Bob, she will encrypt each one before sending it, using a separate key each time.

- Alice is continually faced with the problem of key distribution

- One way to solve the problem is for Alice and Bob to meet up once a week and exchange enough keys to cover the messages that might be sent during the next seven days.

- Exchanging keys in person is certainly secure, but it is inconvenient, not scalable and if either Alice or Bob is sick during winter, the system breaks down.

Even in the digital age, private key encryption on its own struggles with key distribution.

[Q] How’s asymmetric different from symmetric cryptography?

[A] In symmetric cryptography, unscrambling process is simply the opposite

of scrambling. For example, the Enigma machine uses a certain key setting to

encipher a message, and the receiver uses an identical machine in the same key

setting to decipher it. Both sender and receiver effectively have equivalent

knowledge, and they both use the same key to encrypt and decrypt. Their

relationship is symmetric.

In an asymmetric key system, as the name suggests, the encryption key and the decryption key are not identical. This distinction between encryption and decryption keys is what makes an asymmetric cipher special. In an asymmetric cipher, if Alice knows the encryption key, she can encrypt a message, but she cannot decrypt a message. In order to decrypt, Alice must have the decryption key.

[Q] Hold on a minute! I just read the public key cryptography wiki article and I found this:

“Some public key algorithms provide key distribution and secrecy (e.g., Diffie-Hellman key exchange)”

Diffie-Hellman is used to exchange a common shared key, that’s symmetric! Why is it a public key algorithm??

[A] Sharp observation. Diffie-Hellman protocol belongs to a public-key technology. It is an asymmetric technology used to negotiate symmetric keys. Here’s the basic functionality:

- Alice and Bob publicly agree to use a modulus

pand baseg - Alice chooses a secret integer

a, then sends BobA =gamod p - Bob chooses a secret integer

b, then sends AliceB =gbmod p - Alice computes

s =Bamod p - Bob computes

s =Abmod p - Alice and Bob now share a secret

s

Alice’s public key A and Bob’s public key B was sent over a public channel.

Alice’s private key a and Bob’s private key b was kept private.

Hence, this has the context of being a public key cryptography in which both the

parties have a pair of public and private keys.

[Q] While we’re on DHKE, how does Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange work?

[A] When I started to write this article, I thought I could give a brief explanation

of Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange and the discrete logarithm problem.

But the beauty of number theory, hard mathematical problems, properties of prime

numbers is such that, it’s injustice to merely state the protocol

and not explain how math works. It’s not just modulo arithmetic and large

numbers. It deserves it’s own page and explanation.

Here’s an article dedicated to Diffie-Hellman Key Exchange.

[Q] You just said we needed asymmetric encryption because secret key distribution is a problem. But DHKE solved it right?

[A] DHKE is an asymmetric technology used to exchange symmetric keys. Both

parties still had to use the same key to unlock a piece of information.

- Imagine a bank that needs to secure transactions with customers. If there are 100,000 customers, the bank would need to store 100,000 keys and send thousands of messages with customers to establish symmetric keys.

- Imagine an organization with 2000 employees and if each of them need to

communicate with each other securely with a distinct key, the organization

would need 2 million (

n (n - 1)/2) shared secret keys. These problems can be solved by asymmetric keys.

What is RSA?

RSA (Rivest-Shamir-Adleman) is one of the first public-key cryptosystems and is widely used for secure data transmission. Strenth of RSA lies in the practical difficulty of “factoring problem”. RSA has been the industry standard for public key cryptography for many years now.

[Q] Why are we just discussing RSA? What about DSA, ECDSA, Ed25519?

[A] RSA keys are the most widely used and better known. RSA has been around longer

than others, and people trust it more because of the significant time it has

spent in the open world. The longer an algorithm stays in open for academic

studies, strength analysis and deep scrutiny by security community, the higher

the trust. Anyway, there is some information available in the

Additional resources section for those who like

closure.

[Q] How does RSA work?

[A] Here’s a brief and quick summary of RSA:

- Choose two large prime numbers

pandqand calculate their productn = pq - Calculate φ(pq) = (p - 1)(q - 1) and chooses a number

erelatively prime(coprime) to φ(pq). - Calculate the modular inverse

dofemodulo φ(pq). In other words, de ≡ 1 mod φ(n). (dis the private key) - Distribute both parts of the public key:

nande dis kept secret

Let’s keep this article light and reserve deep dives to a dedicated article (Coming soon…).

Generate RSA public-private key pair

Using OpenSSL

# Generating private RSA key

$ openssl genrsa -out openssl_private_key.pem 1024

Generating RSA private key, 1024 bit long modulus

...++++++

.................++++++

e is 65537 (0x010001)

$ cat openssl_private_key.pem

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

MIICXQIBAAKBgQDfmPMQaJba+n3P4E65x7HoHRxmwNl8STPZuIjUMTjSCLfB17FU

Rs9k2yGVSgS24mW6bQnlHy0dW0uDOFd7PqshB/7S2xnP+f+90YBdvT43BKpn1VZ8

...

-----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

# Generating public RSA key using OpenSSL

$ openssl rsa -in openssl_private_key.pem -pubout > openssl_public_key.pub

writing RSA key

$ cat openssl_public_key.pub

-----BEGIN PUBLIC KEY-----

MIGfMA0GCSqGSIb3DQEBAQUAA4GNADCBiQKBgQDfmPMQaJba+n3P4E65x7HoHRxm

wNl8STPZuIjUMTjSCLfB17FURs9k2yGVSgS24mW6bQnlHy0dW0uDOFd7PqshB/7S

2xnP+f+90YBdvT43BKpn1VZ8qMVjGR5xvX9Y/7+I8J4XJTZBNMNXq0Jbq116fLEu

+ylTKsdtS4ewi/U9gQIDAQAB

-----END PUBLIC KEY-----

Using OpenSSH

# -t: Type of key to create

# -b: Number of bits in the key to create

# -N: New passphrase

# -v: Verbose mode

# -f: Filename of key file

$ ssh-keygen -t rsa -b 1024 -N "" -v -f ./id_rsa

Generating public/private rsa key pair.

Your identification has been saved in ./id_rsa.

Your public key has been saved in ./id_rsa.pub.

The key fingerprint is:

SHA256:J9fVZ57aHq2p+cp5WvuqXtKnZ2dVlEZIEf63OVkL8AY <username>@d91513f539fd

The key\'s randomart image is:

+---[RSA 1024]----+

| .+=..|

| .. +.|

| E .o.+|

| .+..o+|

| S o .+ o=|

| + ..+ X|

| ..+O+|

| . *o*B|

| .XBBBo|

+----[SHA256]-----+

$ file id_rsa*

id_rsa: PEM RSA private key

id_rsa.pub: OpenSSH RSA public key

$ cat id_rsa

-----BEGIN RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

MIICXgIBAAKBgQDZjTG1uWYEoO35h7Me4D3R6CmskvQAWf6sc1/o7SwM1CYDusi1

...

2i/mz+FNJOExkkHGu3w/3sPyrW+mCKFLGrWvXJ03IsHDw==

-----END RSA PRIVATE KEY-----

$ cat id_rsa.pub

ssh-rsa AAAAB3N...+w==

DER, BER, PEM, ASN.1, X.509

DER: Distinguished Encoding Rules is a restricted variant of BER (Basic Encoding Rules) for producing unequivocal transfer syntax for data structures described by ASN.1(Abstract Syntax Notation). DER is the same thing as BER with all but one sender’s options removed. DER is widely used for digital certificates such as X.509.

BER: The format for Basic Encoding Rules specifies a self-describing and self-delimiting format for encoding ASN.1 data structures. Each data element is encoded as a type identifier, a length description, the actual data elements, and, where necessary, an end-of-content marker. These types of encodings are commonly called type-length-value or TLV encoding. This format allows a receiver to decode the ASN.1 information from an incomplete stream, without requiring any pre-knowledge of the size, content, or semantic meaning of the data.

PEM: Privacy Enhanced Mail is a de facto file format for storing and

sending cryptographic keys, certificates, and other data, based on a set of

IETF1 standards defining “privacy-enhanced mail.”. Since DER produces binary

output, it can be challenging to transmit the resulting files through systems,

like electronic mail, that only support ASCII. The PEM format solves this

problem by encoding the binary data using base642. PEM also defines a

one-line header, consisting of “-----BEGIN “, a label, and “-----”, and a

one-line footer, consisting of “-----END”, a label, and “-----”. The label

determines the type of message encoded. Common labels include

“CERTIFICATE”, “CERTIFICATE REQUEST”, and “PRIVATE KEY”.

ASN.1: Abstract Syntax Notation One (ASN.1) is a standard interface description language for defining data structures that can be serialized and deserialized in a cross-platform way. ASN.1 is also independent of any hardware or operating system you might choose to use. This allows exchange of information whether one end is a cell phone and the other end is a super computer, or anything in between. It is broadly used in telecommunications and computer networking, and especially in cryptography. ASN.1 is both human-readable and machine-readable.

X.509: A standard defining the format of public key certificates. X.509 certificates are used in many Internet protocols, including TLS/SSL. An X.509 certificate contains a public key and an identity (a hostname, or an organization, or an individual), and is either signed by a certificate authority or self-signed.

Quick summary

- DER is a concrete binary representation used as a wire format to describe ASN.1 schemas

- PEM is nothing more than a base64-encoded DER

[Q] (…yawning) To hell with it. I didn’t understand a thing. What’s all this

boring theory? I skipped over and just scrolled past all those boring words.

Why do I need this?

[A] Yeah, it’s kind of boring and doesn’t make much sense at first. When you are learning A, B, C…Z for the first time, does it make much sense?

Why is this written as A and not as

Why does B come after A and not after C?

Why does alphabets end at Z?

However, “A Lannister always pays his debts” sentence makes sense now because you know the rules of alphabets and the way words are stitched together. It’s pretty similar. Once you understand the format and rules for encoding certificates and keys, you will understand how to read certificates and keys using your favorite programming language/openssl. For now, it’s just a placeholder in case you wish to refer back to this quickly when someone mentions PEM/DER/ASN.1.

Public key cryptography for encryption

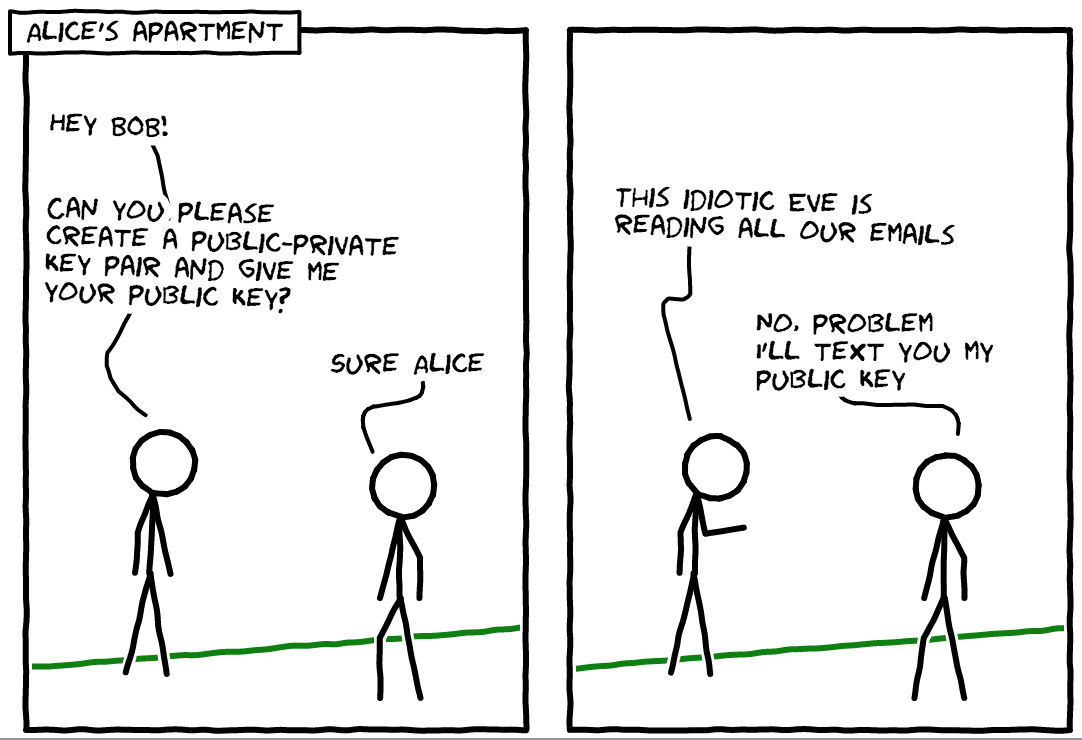

Let’s say Alice wants to send a confidential email to Bob. However, Eve lives in Alice’s apartment and is taking network security course at her grad school. Whenever Eve is jobless and doesn’t have any assignments, she intercepts messages on her network and likes to read others messages.

To overcome this irritating Eve’s eavesdropping habit …

It’s public key, so Eve must have probably intercepted it already, who cares!

- Since RSA public key encryption has limitation on message size, Alice uses a symmetric key and encrypts her confidential email using AES encryption

- Alice encrypts the symmetric key using Bob’s RSA public key and sends both the encrypted symmetric key and encrypted email to Bob

- Eve intercepts both these messages but is unable to decrypt the email since

it’s encrypted using symmetric key and the key can only be decrypted by Bob’s

private key.

Since Eve doesn’t have access to a Quantum computer and hasn’t figured out how to factor the primes of RSA, she’s unable to read Alice’s emails. Alice is happy and the last time I checked, Eve is reading up on Shor’s Algorithm and plans to use IBM Q soon. Until she does that, Alice’s emails are secure.

FYI: This is the basic idea behind PGP (Pretty Good Privacy). Have a look:

Image credits: Wikimedia Commons

[Q] I’ve heard PGP is dead. Is that true?

[A] On 17 May 2018, Wired declared “PGP is dead”.

Without describing Efail vulnerability technically, they

start with their complaint that PGP was first developed in 1991 and science of

cryptography has advanced dramatically since then.

However, the truth is: PGP encryption itself is not broken in any way. The vulnerability is introduced by the user’e email client that processes messages. Saying PGP is broken is just plain wrong, but I guess it generates a lot of clicks.

In a nutshell, if an attacker is able to get access to a user’s encrypted email, they can modify the message in a specific way and send it back to the user. The user’s email client will the decrypt the message and (if the email client is rendering HTML tags) automatically send the decrypted message back to the attacker

“At its core, PGP remains cryptographically sound, and using a few bad

implementations to claim that PGP has a serious flaw is both untrue and

disingenuous.”

- Andy Yen (Founder of Protonmail)

I’ll let Andy from protonmail do the rest of talking : No, PGP is not broken, not even with the Efail vulnerabilities

Public cryptography for signing (digital signatures)

Just imagine if Evil Eve decides to fool around by sending an email to Bob by spoofing Alice? All she has to do is use Bob’s public key to encrypt a random key. Encrypt an email using that random key and send it to Bob as Alice.

Now, you may be thinking “That’s impossible! How can Bob not recognize Alice’s email address? He already knows Alice’s email address is alice@gmail.com”. Okay, what if Eve creates a new email account therealalice@gmail.com and sends out the following email to Bob using above method:

“Hey Bob!

I lost my previous email account password and I think it may be

hacked. So, please ignore all emails from alice@gmail.com and use my new

email address to contact me.

Oh btw Bob! I know this is last minute request but I owe about $5000 to Eve

for my tuition and rental. Today is the last date for Eve to pay her minimum

credit card bill. Could you please be a lamb and transfer $3000 to Eve

before 1pm today?

Here’s Eve’s venmo account: @evilevetrapsyou

Later alligator,

Alice <3 you”

Now please don’t ramble about why Bob never texted/called Alice to confirm this email switch. Just assume Alice left her phone at home or her phone hanged due to an update and Bob couldn’t reach her to verify. Why did Alice leave her phone at home? How would I know? May be she was fed up of charging her phone every 3-4 hours! May be her phone manufacturer sent her an update to deliberately slow down her phone! (Alice hasn’t purchased the latest shiny $1000 phone yet). It could be anything, stop trying to find loopholes and think of a solution instead

Put on your thinking hats now. How do you approve a withdrawal from your bank account using your check? You have to sign it physically for the bank to verify and approve the withdrawal. Your signature proves to the bank that you are authorizing the withdrawal. Similarly, the virtual world has digital signatures. A person can digitally sign an entity and provide a proof of authorization.

For the above example, Alice and Bob both exchange their public keys securely.

- Alice will now take a hash of the message, encrypt the hash using her own private key and append the result to the message

- Eve can of course decrypt this hash using Alice’s public key but hash is of no use

- Even If Eve replaces the hash and the message, Bob won’t be able to use Alice’s public key to decrypt the encrypted hash (remember Eve doesn’t have Alice’s private key to sign a message) and hence won’t believe the message

This is how digital signatures work!

Image source: Wikimedia Commons

When Bob receives the message, he follows these steps:

- Decrypt the signature using Alice’s public key. This will yield a hash of the message

- Decrypt the session key (symmetric) using his private key

- Decrypt the actual message using session key

- Generate a hash of the message

- Check if the generated hash matches the decrypted hash from signature

- If there’s no match, discard the message

- If there’s a match, Alice is the only person on planet earth to send that message since she has the private key

Food for thought

If you notice closely, the above arrangement begins with an assumption:

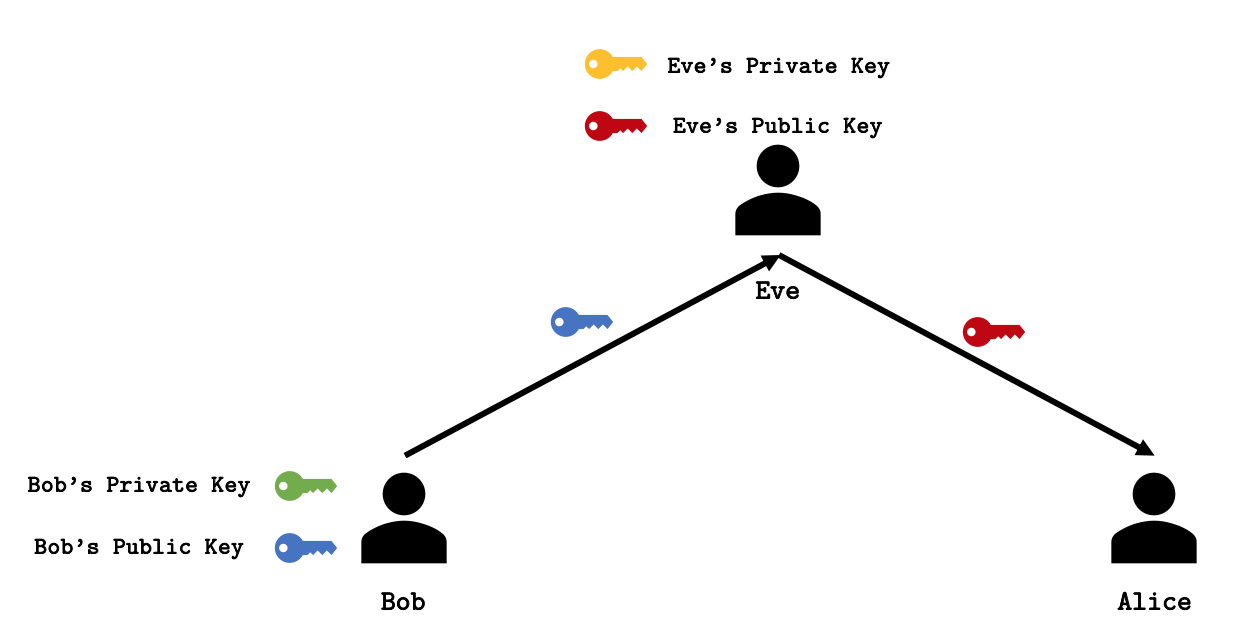

“Alice and Bob both exchange their public keys securely”.

What if Eve intercepts Bob’s public key and replaces it with his own public key? Alice will use Eve’s public key and encrypt her email encryption key. Eve will happily decrypt the email encryption key using her private key. Just to prevent suspicion, Eve may encrypt the email encryption key again using Bob’s public key so that it can be decrypted by Bob. Alice and Bob will happily continue communication without noticing the presence of Eve! Remember that keys are just numbers, there’s no name tag. Even if there’s a tag, Eve will just replace it.

The Remaining Problem: Authenticity of Public Keys

Do we really know that a certain public key belongs to a certain person? In practice, this issue is often solved with what is called certificates.

Create and verify a signature using OpenSSL

Keep the following files ready

- Any file you wish to sign

- A public-private key pair (refer this)

- Let’s say the publickey is

publickey.pub - Let’s say the private key is

private.pem

- Let’s say the publickey is

# Create a signature file signature.sha256 for a plaintext file foo.txt

$ openssl dgst -sha256 -sign private.pem -out signature.sha256 foo.txt

$ file signature*

signature.sha256: data

# Verify the signature for foo.txt

$ openssl dgst -sha256 -verify publickey.pub -signature signature.sha256 foo.txt

Verified OK

# To test verification, modify the plaintext file (Add a random character)

$ echo "a" >> foo.txt

# See if the signature matches now

$ openssl dgst -sha256 -verify publickey -signature signature.sha256 foo.txt

Verification Failure

Where,

dgst: perform digest operations

-sha256: Name of a digest

-sign filename: Digitally sign the digest using the private key in "filename"

-out: Filename to output to

-verify filename: Verify the signature using the public key in "filename"

-signature: The actual signature to verify

[Q] Can I encrypt a file with my private key and decrypt using public key?

[A] Just think of this operation and see if it makes sense. Encrypting with

your private key doesn’t make much sense when the decryption key is well known

and public. You might as well give the file in plaintext to the world.

Additional resources

-

RSA, DSA, ECDSA, and Ed25519 are all used for digital signing

- DSA (Digital Signature Algorithm) is a Federal Information Processing

Standard for digital signatures. It’s security relies on a discrete

logarithmic problem. Compared to RSA, DSA is faster for signature

generation but slower for validation. Compare it yourself using your

openssl toolset:

$ openssl speed dsa ... sign verify sign/s verify/s dsa 512 bits 0.000667s 0.000794s 1499.2 1258.8 dsa 1024 bits 0.002285s 0.002750s 437.6 363.6 dsa 2048 bits 0.008332s 0.009960s 120.0 100.4 $ openssl speed rsa ... sign verify sign/s verify/s rsa 512 bits 0.000706s 0.000038s 1416.0 26280.2 rsa 1024 bits 0.004336s 0.000191s 230.6 5237.8 rsa 2048 bits 0.029155s 0.000825s 34.3 1212.6 rsa 4096 bits 0.198824s 0.003049s 5.0 327.9This matters because we generate (sign) the key once but end users verify it way more often. Current processors for desktops and laptops are ridiculously fast. It can be an issue on embedded devices

- ECDSA is an Elliptic Curve implementation of DSA (Digital Signature Algorithm). Elliptic curve cryptography3 is able to provide the relatively the same level of security level as RSA with a smaller key

- Ed25519 is similar to ECDSA but uses a superior curve, and it does not have the same weaknesses when weak RNGs4 are used as DSA/ECDSA. There’s some conspiracy theory as well, but that’s a topic for another day.

- DSA (Digital Signature Algorithm) is a Federal Information Processing

Standard for digital signatures. It’s security relies on a discrete

logarithmic problem. Compared to RSA, DSA is faster for signature

generation but slower for validation. Compare it yourself using your

openssl toolset: